Conflicting Attitudes and Actions: Cognitive Dissonance Explained

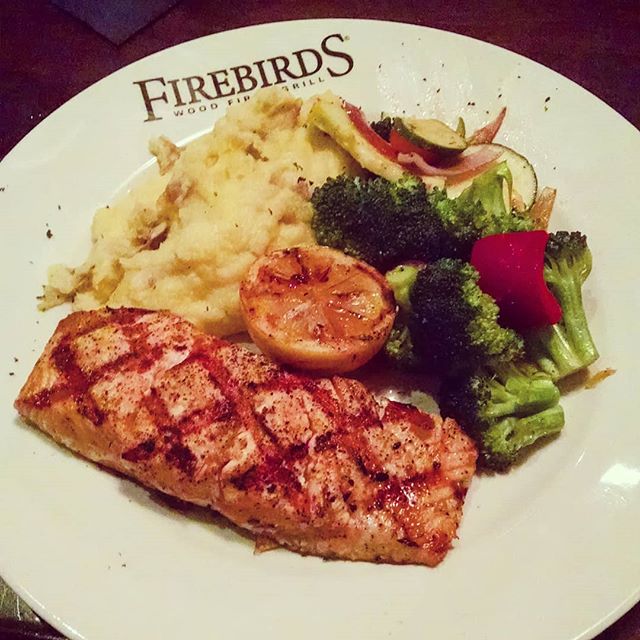

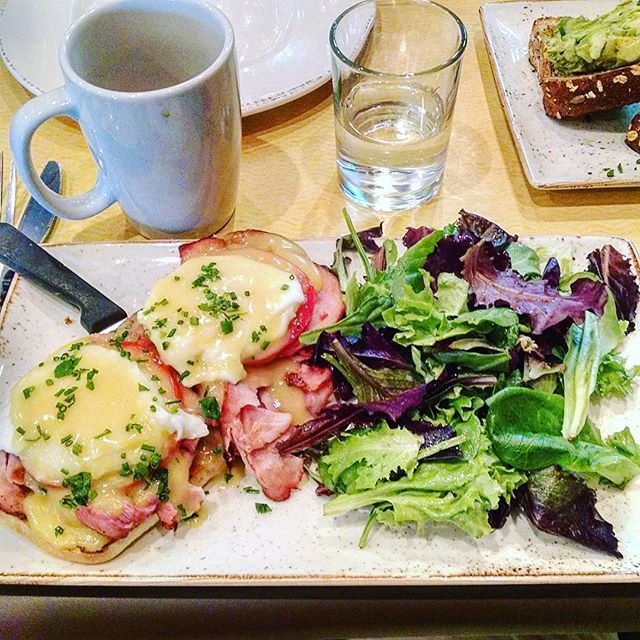

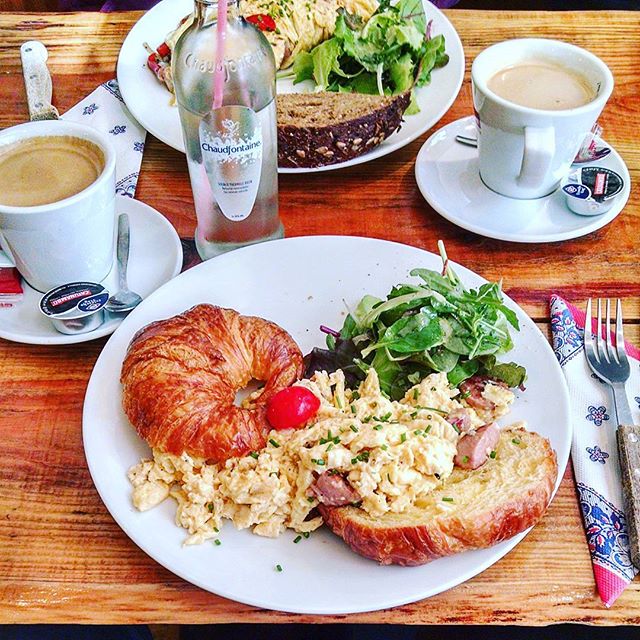

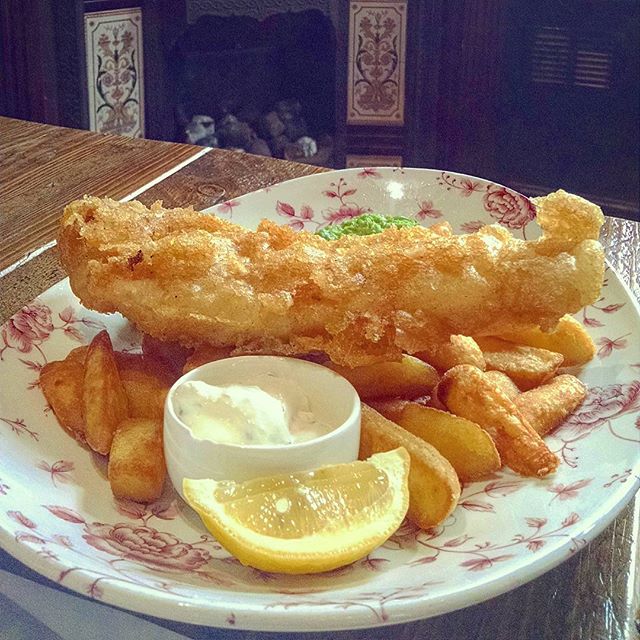

/Let me paint a picture for you. Someone you know is an avid animal rights enthusiast. They post on social media all sorts of animal rights pictures and information. They talk about how "we're all animals" just about every other conversation with them. Not to mention their huge beef with the meat industry (oh MAN I'm funny). But here's the thing, even after all of these firmly held beliefs that we should treat animals the way we treat humans, you watch this person still eat meat. "How can they do this?" you ask yourself. "Aren't these ideologically conflicting principles? Does eating meat make this person a hypocrite?"

The answer is yes – sort of. You see to this person, there is some form of justification going on in their minds that makes it okay for them to eat meat. To them, maybe being such a huge animal rights activist alleviates the damage caused by them eating meat, making it moot and thus justified. Maybe they only eat organic, grass-fed, responsibly raised meat from local farms. Maybe they only eat chicken because chickens aren't as cute as cows or pigs. Regardless, to this person they have somehow justified and reconciled the conflicting principles of: the meat industry is bad, and it's okay for me to eat meat.

This extremely common psychological phenomenon is called cognitive dissonance. Jarcho, Berkman, and Lieberman define cognitive dissonance in their 2011 article published by Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience entitled, The neural basis of rationalization: cognitive dissonance reduction during decision-making, as: "an aversive psychological state aroused when there is a discrepancy between actions and attitudes". In other words, when there is an inconsistency between what we do and what we believe, we become intensely uncomfortable. So our brain has to do some work and justify to ourselves within our set of beliefs that what we do is okay. There are three ways we do this.

The first way we reduce the aversion that's caused by cognitive dissonance is by changing our attitudes. This way, our actions no longer present a problem, as the attitude we had has been altered. Maybe the person who eats meat, instead of thinking the entire meat industry is bad, they change their belief to only thinking that only the industrialized meat industry is bad. This way they could eat free range, grass-fed, organic, locally and responsibly raised meat products, while still being within the confines of their belief, alleviating the discomfort from their cognitive dissonance. It is however, as I’ve talked about in a previous post about being stubborn, not super easy to change one’s beliefs. People will still do this in order to resist cognitive dissonance, as the discomfort is really that powerful.

Another way we reduce dissonance is by gathering new information that cancels out or outweighs the belief. The classic example of this is the smoker who finds out research hasn't proven a direct causal link between smoking and lung cancer, making it okay for that person to smoke. With our example, the person who's an avid animal rights activist may have discovered that with every three posts on social media about animal rights they share, two animals are saved in the process (I'm just making this up for the sake of the example, I don't have any statistics on social-media-posts-per-animal-saved, although here is an interesting statistic that shows how many animals per year being completely vegetarian saves. Spoiler: it's over 300). With this new information, our friend can justify to themselves: "well if I share three posts on social media, I'm saving two animals, so eating one is still net more positive for the animals." The new information still keeps both the belief and the behavior intact and allows for the behavior to exist in the world of the belief.

The third way to alleviate the discomfort from cognitive dissonance is to decrease how important the belief is. By reducing the importance of the belief, we can much more easily allow ourselves to partake in an action that conflicts with it. Maybe our friend thinks that as long as they don't see the injustice take place it's okay to eat the meat it creates. Or perhaps they think, "well people and animals die every day so it's okay for me to eat them if that's already happening". They also could think that abstaining from meat isn't a huge deal anymore, or that only eating the “cute” animals is bad. All of these would lessen how important that belief is to them, thus making their action more okay.

You may be wondering, "Wait a minute, we changed our attitudes, added new information, shouldn’t we be able to change our behavior to decrease cognitive dissonance?" Well if we don't engage in a behavior, then our beliefs haven't been violated, and thus no dissonance occurs. Also cognitive dissonance most frequently happens after decisions are made, and the discomfort is felt after doing an action that falls out of line with our attitudes. Jarcho and colleges discuss how cognitive dissonance is at play during difficult decision-making processes. They postulate that we often change our attitudes in order to stay consistent with our actions and decisions especially when we make very difficult decisions and have to justify that decision to ourselves. They find that when making difficult decisions, people can change their attitudes very rapidly based on the decisions they've made. These cognitive processes occur remarkably fast, and even when making many decisions in quick succession. Basically, our brain is willing to work as hard as possible to justify the decisions we make.

According to Egan, Santos, and Bloom in their 2007 article The Origins of Cognitive Dissonance: Evidence From Children and Monkeys published in Psychological Science, both children and monkeys will change their preferences to match their past decisions and avoid dissonance. Their findings are actually pretty interesting, as they find that because children have relatively little past experiences with decision-making their results suggest that reducing cognitive dissonance is something that's ingrained into our psyches from birth. They speculate that there is evidence supporting the idea that it doesn't take higher level brain functions like language to be able to engage in trying to alleviate cognitive dissonance, granting credence to the notion that cognitive dissonance reduction is inherent in us.

What does this mean? This means that it is not only natural for us to want to decrease cognitive dissonance discomfort, but it’s a simple process hardwired into the framework of our brains. When we feel that aversion due to conflicting behaviors and beliefs, our very sense of self is attacked. It's our brain saying to us "you are a hypocrite, and thus you are not as important, significant, or good as others," jeopardizing our perception of purpose in life. However when we justify our actions by one of the three ways discussed above, we think, "I am not a hypocrite, and thus I am not unimportant, insignificant, or bad," validating our existence and purpose in life. Decreasing the discomfort from cognitive dissonance is part of what makes us alive and human.

Cognitive dissonance is one of the most common phenomenon in life, which makes sense as there’s evidence to suggest that it is naturally a part of our psyches. In order to alleviate the aversion caused from conflicting behaviors and beliefs, we can either change the belief, add new information to outweigh the belief, or make the belief less important. We justify decisions and actions of people all the time, but justifying those actions to ourselves is what our brains will work the hardest to do. It turns out we’re far more concerned with being a person who’s consistent with our own beliefs, than we are with other peoples’ beliefs and behaviors.

-

May 2018

- May 10, 2018 This Or That: How Useful Are Dichotomies Really? May 10, 2018

- May 3, 2018 Which One Are You? Promotion and Prevention Focus May 3, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 26, 2018 Are You Irrational? Behavioral Economics Explains Decision-Making Apr 26, 2018

- Apr 19, 2018 Can You Convince Me? The Art Of Persuasion Apr 19, 2018

-

November 2017

- Nov 15, 2017 Who Do You Think You Are? How Labels Influence Identity Nov 15, 2017

-

October 2017

- Oct 25, 2017 Why Are All My Friends Getting Married? Relationship Contingency And Marriage Oct 25, 2017

- Oct 18, 2017 Passion And Obsession: When Does What You Love Become Excessive? Oct 18, 2017

- Oct 11, 2017 Does A Home Field Advantage Really Exist? Oct 11, 2017

- Oct 4, 2017 Mass Shootings and Mental Illness Oct 4, 2017

-

September 2017

- Sep 27, 2017 Child Development In The Internet Age: Delay Discounting Sep 27, 2017

- Sep 20, 2017 Should I Take All My Tests Drunk? State-Dependent Retrieval Sep 20, 2017

- Sep 13, 2017 Why We Don't Help Those In Need: The Bystander Effect Sep 13, 2017

- Sep 6, 2017 Is Ignorance Really Bliss? The Dunning-Kruger Effect Sep 6, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 30, 2017 Conflicting Attitudes and Actions: Cognitive Dissonance Explained Aug 30, 2017

- Aug 23, 2017 Are You Easily Distracted? Why We Have Trouble Focusing Today Aug 23, 2017

- Aug 16, 2017 The Psychology of Hate Aug 16, 2017

- Aug 9, 2017 Road Rage and Riots Aug 9, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 19, 2017 What To Do When Faced With Too Many Options: Choice Overload Jul 19, 2017

- Jul 12, 2017 Out of Control: Perceived Fear of Self-Driving Cars Jul 12, 2017

- Jul 5, 2017 Nobody Likes Losing: Loss Aversion Explained Jul 5, 2017

-

June 2017

- Jun 28, 2017 Why Is The Grass Always Greener? Jun 28, 2017

- Jun 21, 2017 Why People Are So Stubborn: Confirmation Bias Jun 21, 2017

- Jun 14, 2017 Why Do We Do Anything? Operant Conditioning Explained Jun 14, 2017

- Jun 7, 2017 Obsession with Nostalgia Jun 7, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 13, 2017 Has Technology Killed Love? May 13, 2017

- May 13, 2017 Music and Attention May 13, 2017

- May 13, 2017 What is Brain Food? May 13, 2017