What To Do When Faced With Too Many Options: Choice Overload

/Do you ever spend half an hour scrolling through Netflix trying to find something new and interesting to watch but then just end up watching the same episodes of Friends you always do? Well it turns out there's actually a psychological phenomenon to explain why we do that! It's called choice overload.

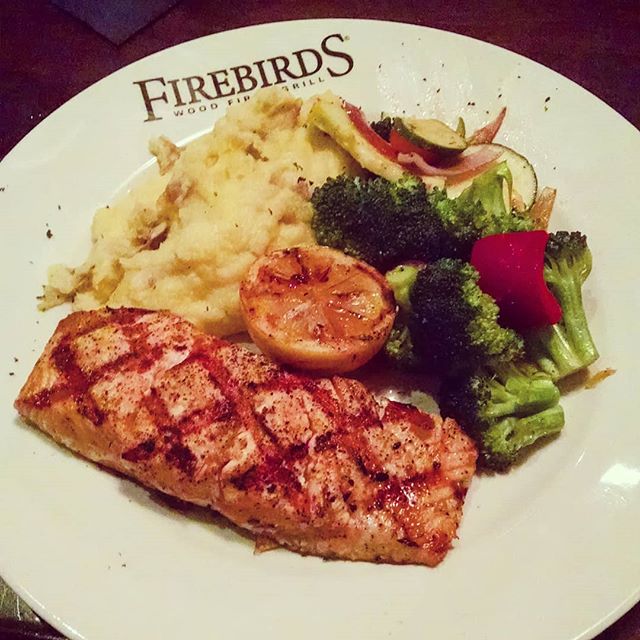

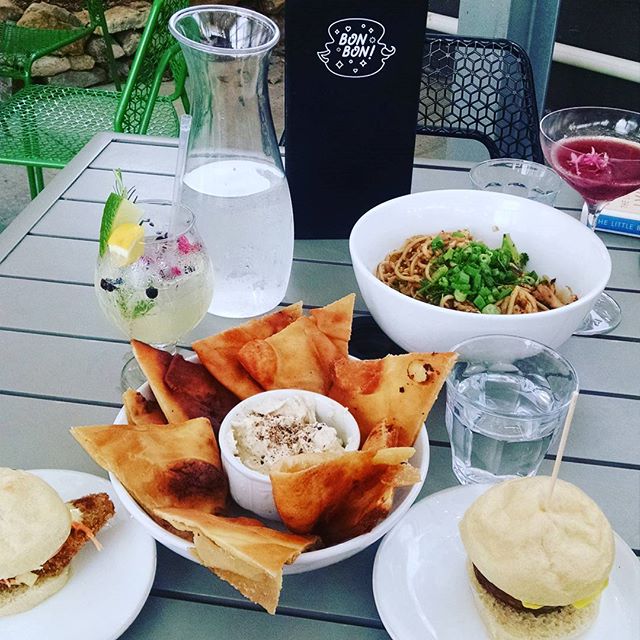

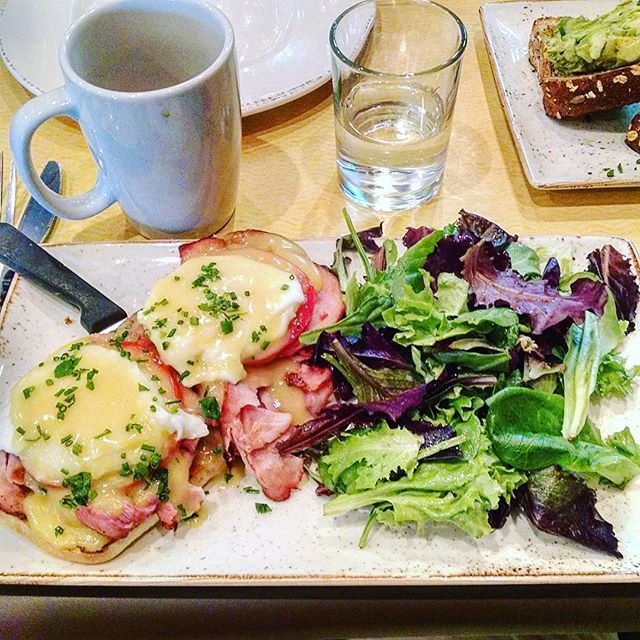

Deciding can often be extremely difficult, especially today in a world where we are constantly bombarded with countless choices on a regular basis. I turn on my phone and am flooded with different apps, pictures, and posts I can click on that are vying for my attention. Such is the world we live in now; things that get more clicks get more traffic, get more likes, and thus people are spending the most amount of time on those things. When we are inundated with so many options, we become overwhelmed extremely quickly. What am I going to eat? Where should I go on vacation? What music should I listen to? What movie or TV show should I watch? When there are so many choices, how then are we supposed to make any decisions at all?

Our brains are wired to function on what are called heuristics, or mental shortcuts. We want to minimize the amount of cognitive stress, or work our brains have to do, so we create shortcuts to make those processes easier. They're sort of like a rule of thumb for quicker cognition. For example, if someone is describing to you a fruit that’s yellow, you're going to almost immediately think of a banana, because bananas are fruit we very commonly come into contact with regularly, making it easier for our brain to call forth that image. Usually you would be calling to mind the fruit that that person intended you to. However a similarly yellow fruit, the quince (native to largely European and Middle Eastern regions) would take a lot more work to try and think of because we aren't usually as familiar with them (here's what they look like in case you're curious). Also to answer your question, yes I did just Google obscure yellow fruits to demonstrate what heuristics are.

When we are presented with a lot of options to choose from, we fall back on those heuristics pretty heavily. See, when faced with all these different choices, instead of weighing the pros and cons of each individual option, we choose the easiest option. More often than not that option is the default option - which sometimes means no option at all. If I need new shoes but have no idea what kind of shoes I want, I'm going to choose the default of sticking to my current beat up and worn out shoes as opposed to trying to figure out which shoe type, style, and price is best for me. If I have to choose between watching all of the new shows on Netflix, instead of figuring out which shows suit my preferences, and gauging what I’m in the mood to watch, and going through all the reviews of each show, I'm just going to stick with something I know I will enjoy, because I have in the past, i.e. that episode of Friends with the trivia game show.

A 2007 study by Sheena S. Iyengar from Columbia University, and Emir Kamenica from University of Chicago found that "increasing the size of the choice set strengthens the appeal of easier-to-understand options". This means that the higher the amount and complexity of choices incentivizes us to choose the simplest option. I don't want the cable option with all the bells and whistles I just want basic cable and internet. That's why cable companies always have premium options, because they know they'll get more people to buy into the basic plan, which they can control the price of, while they still have the premium option for people who are going to pay that extra amount of money anyway. When faced between the $80 basic plan, the $90 premium plan, the $100 super premium plan, the $110 super ultra premium plan, that company knows they're going to make at least $80 off most consumers when buying cable because they know people will chose the simpler option, even if that option isn't that much less expensive than the complex options.

Newer research is starting to expand upon this phenomenon of choice overload. A super interesting 2012 study by Evan Polman from New York University, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, titled Effects of Self–Other Decision Making on Regulatory Focus and Choice Overload, found that we actually choose differently when we're making decisions for ourselves as opposed to making decisions for others. Polman found, in the culmination of five experiments, that when we choose for others we focus more on promotion, and when we choose for ourselves we focus more on prevention. So if I'm helping my friend decide where to go on vacation, I'm going to want to promote them having a great time, thus influencing my decision for them to go somewhere exciting and new like the Caribbean. If I'm deciding for myself where to go on vacation, I'll be more focused on preventing a loss of money or security, so I'll be more likely to choose a safer option like the beach a few hours away.

These studies Polman conducted find that when choosing for others, people are more likely to take risks and gather more information regarding the promotion of a quality experience. This is because the risk assessment for us is low in these situations. We know we aren't going to lose much if someone else has a bad experience. Likewise when choosing for ourselves, we're less likely to take risks because, as I discussed in a previous post about loss aversion, we are wired to hate to lose things. So when we experience choice overload when trying to decide something for ourselves, we choose the lowest risk option, which is usually the default or no option at all. When we experience what Polman describes as reverse choice overload while deciding for others, we do much more research and try to figure out the best option for that person in terms of enjoyment and promotion.

We often believe that people who make decisions for others are more detached and thus more objective, resulting in them making more sound decisions. People making decisions for someone else fall prey to less cognitive biases. Lawyers, for example can often see the opposing side’s arguments much more clearly than the person they’re defending, because they’re less attached to the case. Polman’s studies however suggest that those representatives actually have potentially more cognitive bias, because they’re so focused on promotion they can neglect or undervalue some of the risk.

How many times has someone asked you what you're watching on Netflix? This is likely in part due to choice overload. They're looking for recommendations for a low risk option for them to spend their valuable time and attention on. We use these heuristics in order to solve complex problems quickly, which often results in us choosing the simplest option in a situation where we're faced with choice overload. When choosing for others we're more promotion focused and when choosing for ourselves we're more prevention focused. So next time you're having trouble making a decision, ask somebody else what they would decide for you, because chances are they're likely be cognitively inclined to promote a positive outcome for you.

Thanks for reading this week's Brain Food! Let me know what you think in the comments down below, give this post a like, or send me an email at brainfood@brainfoodblog.com with questions, criticisms, or suggestions for future posts.

-

May 2018

- May 10, 2018 This Or That: How Useful Are Dichotomies Really? May 10, 2018

- May 3, 2018 Which One Are You? Promotion and Prevention Focus May 3, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 26, 2018 Are You Irrational? Behavioral Economics Explains Decision-Making Apr 26, 2018

- Apr 19, 2018 Can You Convince Me? The Art Of Persuasion Apr 19, 2018

-

November 2017

- Nov 15, 2017 Who Do You Think You Are? How Labels Influence Identity Nov 15, 2017

-

October 2017

- Oct 25, 2017 Why Are All My Friends Getting Married? Relationship Contingency And Marriage Oct 25, 2017

- Oct 18, 2017 Passion And Obsession: When Does What You Love Become Excessive? Oct 18, 2017

- Oct 11, 2017 Does A Home Field Advantage Really Exist? Oct 11, 2017

- Oct 4, 2017 Mass Shootings and Mental Illness Oct 4, 2017

-

September 2017

- Sep 27, 2017 Child Development In The Internet Age: Delay Discounting Sep 27, 2017

- Sep 20, 2017 Should I Take All My Tests Drunk? State-Dependent Retrieval Sep 20, 2017

- Sep 13, 2017 Why We Don't Help Those In Need: The Bystander Effect Sep 13, 2017

- Sep 6, 2017 Is Ignorance Really Bliss? The Dunning-Kruger Effect Sep 6, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 30, 2017 Conflicting Attitudes and Actions: Cognitive Dissonance Explained Aug 30, 2017

- Aug 23, 2017 Are You Easily Distracted? Why We Have Trouble Focusing Today Aug 23, 2017

- Aug 16, 2017 The Psychology of Hate Aug 16, 2017

- Aug 9, 2017 Road Rage and Riots Aug 9, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 19, 2017 What To Do When Faced With Too Many Options: Choice Overload Jul 19, 2017

- Jul 12, 2017 Out of Control: Perceived Fear of Self-Driving Cars Jul 12, 2017

- Jul 5, 2017 Nobody Likes Losing: Loss Aversion Explained Jul 5, 2017

-

June 2017

- Jun 28, 2017 Why Is The Grass Always Greener? Jun 28, 2017

- Jun 21, 2017 Why People Are So Stubborn: Confirmation Bias Jun 21, 2017

- Jun 14, 2017 Why Do We Do Anything? Operant Conditioning Explained Jun 14, 2017

- Jun 7, 2017 Obsession with Nostalgia Jun 7, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 13, 2017 Has Technology Killed Love? May 13, 2017

- May 13, 2017 Music and Attention May 13, 2017

- May 13, 2017 What is Brain Food? May 13, 2017