Why Do We Do Anything? Operant Conditioning Explained

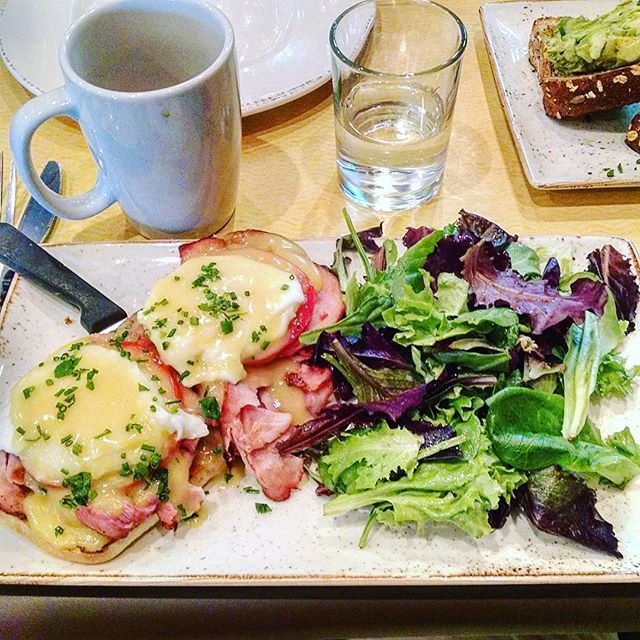

/Why do we do what we do? It's actually really simple, and in fact human behavior is extremely predictable. Have you ever heard of Operant Conditioning? Probably in some Psych class you had to take to graduate, or casually at a bar out with friends (if your friends are nerds like myself). Why do we eat pizza or watch Netflix or procrastinate? Well the super simple answer is: because we like to. The less-simple-but-still-pretty-simple answer is: because we learn to like to.

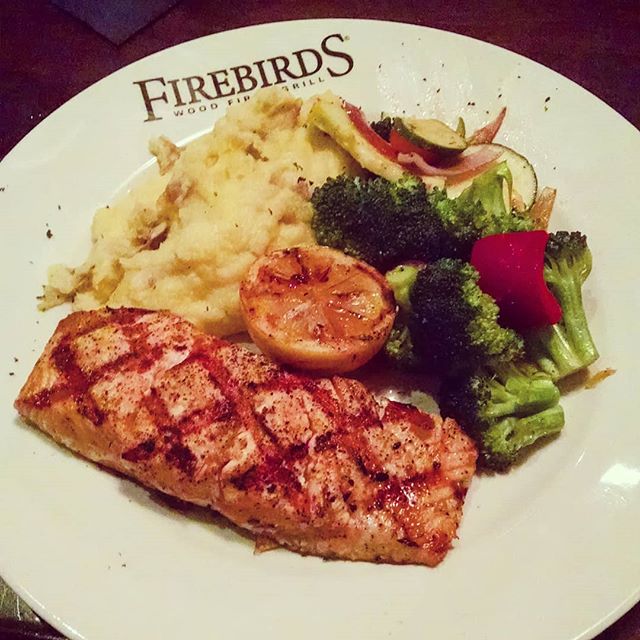

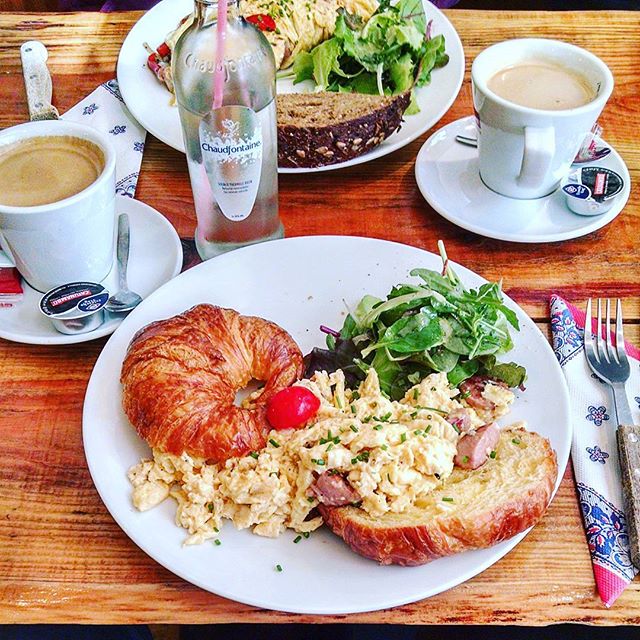

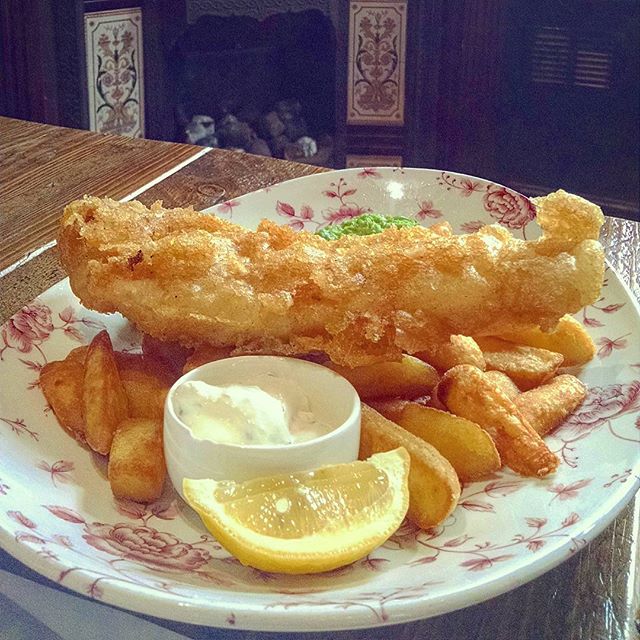

Operant Conditioning is really just a fancy way of talking about learning. At the center of Operant Conditioning is the concept of positive reinforcement. This is functionally a reward for doing a thing that incentivizes us to continue to do that thing in the future. So, we eat pizza because it tastes good. We've learned that pizza tastes good, which incentivizes us to continue eating it in the future for that reward of it tasting good. Real simple right?

This may seem like the most self-explanatory, intuitive thing in the world, but bear with me. Operant conditioning can explain so much of human behavior, from procrastinating, to working, to choosing our friends. We can even use Operant conditioning to change behavior. At the heart of all of these concepts is positive reinforcement which is why I wanted to make sure we established that first.

Okay why do we go to a job we hate every day? That's not positive reinforcement right? If anything that should be a reason for us to quit. Well sort of. Turns out money is a HUGE reinforcer for us. So even if we have to sit in hours of traffic or go to work to get chewed out by a boss that hates us, we stay because we've learned that the paycheck we earn can be used to buy things that we like and need. Working at that job means we can afford to buy cable and Netflix, and go out for drinks with friends to get our minds off of working. Not to mention the fact that we literally need money to survive in our world because it helps us by food (like pizza) and shelter and transportation. We like having food and shelter and transportation more than we dislike working at the job, so often times people will just take the abuse and the punishment because it eventually leads to a strong reinforcer (reinforcers are stronger when they're necessary for survival, we've found this with studies involving rats and food, etc.).

Why do we choose the friends we do? Simple, because we've learned that spending time with these friends is preferable to not spending time with them, or preferable to spending time with others. These friends make us laugh and we're happy with them, which we enjoy, so we are incentivized to continue to hang out with them in the future. Maybe Group A of friends is a lot of fun and we always have a good time with them, and Group B of friends are, you know fine, but we don't have as good of a time as we do with Group A, or it's more difficult to try and coordinate spending time with Group B. We'll predictably choose to spend more of our time with Group A than Group B, because we feel a greater amount of reinforcement for doing a lesser amount of work. People don't like doing work, but do like feeling good, so we try to minimize the amount of work we do and maximize the amount of pleasure we get from something. This is a basic principle of human behavior that drives most of our decisions.

Still with me? Okay now I'm going to get into timed reinforcers. So lets say a reinforcer is delivered to a subject whenever they press a lever. Subject presses lever -> reinforcer is delivered. That subject is going to press the lever as many times as it wants, but not be as concerned with how many times or when they push the lever because they know that whenever they press that lever, a reinforcer is delivered every time.

Now lets say that when they press the lever the reinforcer is delivered, but now the reinforcer won't be delivered until 60 seconds has passed since the last delivery. At first, the subject will press the lever a lot, but once they learn the schedule, they will start to only press the lever a few times towards the end of that 60 seconds. This is because it's less work for the same amount of reinforcement. That subject understands they can push the lever towards the beginning a lot of times, but nothing will happen because they won't get reinforced until 60 seconds has passed, so therefore it's inefficient for them to expend work for not getting anything in return, when they can do a lesser amount of work and still get reinforced after that 60 seconds has passed. If I know I can wait until the last minute, do an amount of work, and then get reinforced, why would I work harder towards the beginning when I know the result will be the same?

This is why people procrastinate. It's a predictable human behavior that people will try to do as little work as possible to get the most they can. If I know that I can cram for a test at the end of the week during the last day or so and get a decently good grade on it, why would I start studying earlier on in the week and experience relatively similar results? I don't want to work harder than I have to in order to get reinforced.

There's your crash course in Operant Conditioning. We do things we like. We do things more often because we learn to like them. We want to get rewarded as much as possible for doing as little work as possible. So much of human behavior can be explained using these super simple principles. If you want me to go more in depth on another topic like this, or explain a certain example of human behavior through Operant Conditioning leave a comment below or email me at brainfood@brainfoodblog.com!

-

May 2017

- May 13, 2017 What is Brain Food? May 13, 2017

- May 13, 2017 Music and Attention May 13, 2017

- May 13, 2017 Has Technology Killed Love? May 13, 2017

-

June 2017

- Jun 7, 2017 Obsession with Nostalgia Jun 7, 2017

- Jun 14, 2017 Why Do We Do Anything? Operant Conditioning Explained Jun 14, 2017

- Jun 21, 2017 Why People Are So Stubborn: Confirmation Bias Jun 21, 2017

- Jun 28, 2017 Why Is The Grass Always Greener? Jun 28, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 5, 2017 Nobody Likes Losing: Loss Aversion Explained Jul 5, 2017

- Jul 12, 2017 Out of Control: Perceived Fear of Self-Driving Cars Jul 12, 2017

- Jul 19, 2017 What To Do When Faced With Too Many Options: Choice Overload Jul 19, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 9, 2017 Road Rage and Riots Aug 9, 2017

- Aug 16, 2017 The Psychology of Hate Aug 16, 2017

- Aug 23, 2017 Are You Easily Distracted? Why We Have Trouble Focusing Today Aug 23, 2017

- Aug 30, 2017 Conflicting Attitudes and Actions: Cognitive Dissonance Explained Aug 30, 2017

-

September 2017

- Sep 6, 2017 Is Ignorance Really Bliss? The Dunning-Kruger Effect Sep 6, 2017

- Sep 13, 2017 Why We Don't Help Those In Need: The Bystander Effect Sep 13, 2017

- Sep 20, 2017 Should I Take All My Tests Drunk? State-Dependent Retrieval Sep 20, 2017

- Sep 27, 2017 Child Development In The Internet Age: Delay Discounting Sep 27, 2017

-

October 2017

- Oct 4, 2017 Mass Shootings and Mental Illness Oct 4, 2017

- Oct 11, 2017 Does A Home Field Advantage Really Exist? Oct 11, 2017

- Oct 18, 2017 Passion And Obsession: When Does What You Love Become Excessive? Oct 18, 2017

- Oct 25, 2017 Why Are All My Friends Getting Married? Relationship Contingency And Marriage Oct 25, 2017

-

November 2017

- Nov 15, 2017 Who Do You Think You Are? How Labels Influence Identity Nov 15, 2017

-

April 2018

- Apr 19, 2018 Can You Convince Me? The Art Of Persuasion Apr 19, 2018

- Apr 26, 2018 Are You Irrational? Behavioral Economics Explains Decision-Making Apr 26, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 3, 2018 Which One Are You? Promotion and Prevention Focus May 3, 2018

- May 10, 2018 This Or That: How Useful Are Dichotomies Really? May 10, 2018